Leadership—the 21st Century Enlightenment

Kenneth Miller | Updated August 2025

Copyright © September 2017 ACT Advisory LLC

“The demands on the skill, knowledge, performance, responsibility and integrity of the manager have doubled in every generation during the past half century.”

—Peter Drucker,

The Practice of Management, 1954

Little could Drucker have known over seven decades ago just how prophetic that bit of retrospective would prove to be. But though the demands he cites continue to grow geometrically, it’s an open question whether many contemporary leaders are possessed of the requisite skills, knowledge, responsibility and integrity to meet the challenges of a new-ish millennium. But a perhaps more intriguing question is whether most leaders were then or are now—some three generations later—able or willing to adapt.

Demographics, technology–and now pandemic–have conspired to quite literally revolutionize the conduct of business—a Technological Renaissance one might say. This phenomenon is testing the conventional wisdom about everything from organization structure and culture to long-held beliefs about how leaders should think and act. Some call it Creative Destruction. Others characterize it as chaos. We think it healthy. And yes, we are persuaded that most leaders are indeed able to adapt—and adapt they must if they’re to create and drive the organizational cultures required to meet these challenges.

The open question is one of willingness. If the rapidly changing technology and environment constitute a latter-day Renaissance, leadership may require a 21st century version of The Enlightenment.

Some attribute these rapid changes to the influx of millennials–and now Gen-Zers–bringing new and different values into the workplace. One observer wrote:

“The children now love luxury. They have bad manners,

contempt for authority;

they show disrespect for [their] elders and love chatter…”

Oh, wait—that was Socrates some 2500 years ago. The more some things change, the more they stay the same.

Oh, wait—that was Socrates some 2500 years ago. The more some things change, the more they stay the same.

For example, in their recent book, The New One Minute Manager, Ken Blanchard and Spencer Johnson point out that top-down leadership was a way of life when they wrote the first version of the book well over thirty years ago, but that today, “…a new, more collaborative approach to leading and motivating people” is required. “These days effective [emphasis added] leadership is more of a side-by-side relationship”, they write. But indeed, the prescription for effective leadership Blanchard and Johnson offer today is really not all that different from that which they advocated over three decades ago.

And therein lies the real ‘Secret’.

The Secret to great leadership is this:

THERE IS NO SECRET!!

Notwithstanding the evolving circumstances and influences confronting us today, pretty much everything we need to know about what it takes to lead effectively here in the third millennium has been known since at least the middle of the 20th century—well over 60 years ago. This is not an original thought. Tom Peters—of In Search of Excellence fame—recently wrote:

“Doug McGregor and Abe Maslow invented millennials-friendly

21st century leadership over a half century ago”

But as ancient Chinese Philosopher Confucius admonished:

“The essence of Knowledge, once possessed,

is the use one makes of it”

Otherwise put, what we know is only as valuable as the extent to which it influences our behavior. Therein lies the proverbial ‘rub’.

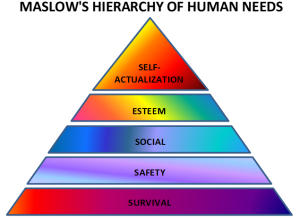

The pyramidal depiction of Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs theory diagrammatically provides what is still the simplest, most comprehensible basic explanation of human behavior and motivation, an understanding of which is essential in any organization expecting to be genuinely and sustainably successful.

Notwithstanding lively and long-running debate regarding Maslow’s theory in psychology circles, its wide acceptance and longevity are testament to its usefulness and practicality. Our focus here, though, will generally be on the work of Douglas McGregor and his acolytes in applying Maslow’s concepts in the workplace.

McGregor’s Theories X and Y of workforce behavior, developed in the 1950s and ‘60s at MIT, are implicit in much of what has since been written about leadership, management and organization development.

Theory X embodies the assumption that workers are inherently lazy and will avoid work if, when and where they can. Thus, the theory goes, employees need to be closely supervised and comprehensive systems of controls developed. A rigidly hierarchical structure is required with a narrow span of control at each level. According to Theory X, employees will show little ambition without an enticing incentive program or fear of punishment, and will avoid responsibility whenever they can. Employees—perhaps people in general—are not to be trusted, and the allocation of blame is a major supervisory function. You may hear this referred to as accountability, but as Harvard’s Pasi Sahlberg puts it:

Theory X embodies the assumption that workers are inherently lazy and will avoid work if, when and where they can. Thus, the theory goes, employees need to be closely supervised and comprehensive systems of controls developed. A rigidly hierarchical structure is required with a narrow span of control at each level. According to Theory X, employees will show little ambition without an enticing incentive program or fear of punishment, and will avoid responsibility whenever they can. Employees—perhaps people in general—are not to be trusted, and the allocation of blame is a major supervisory function. You may hear this referred to as accountability, but as Harvard’s Pasi Sahlberg puts it:

“Accountability is what’s left when responsibility is subtracted”

Of course, the notion that others are motivated only by coercion or monetary reward leads inevitably to an authoritarian culture and leadership style, the oppressive pessimism of which subverts morale, engagement and productivity. This seemingly anachronistic mindset—and its implicit assumption that ‘leadership’ and ‘management’ are somehow immune to these behavioral influences—has been with us since well before Adam Smith, but is even today not as uncommon as we might like to think. The ‘we/they’ paradigm is very much alive and unwell here in the third millennium.

Theory Y, on the other hand, acknowledges the possibility–indeed the likelihood–that employees may be ambitious, self-motivated and anxious to accept greater responsibility for the content, method and outcome of their work. It assumes that, given the chance, employees may well desire to be creative and forward-thinking in the workplace, thus obviating the need for excessive work rules, giving workers freedom to perform at their best, increasing productivity and generally making life wonderful for one and all—OK, that may be a bit of an overstatement. McGregor urged only that leaders and managers be open to a more optimistic perception of workers and the behavioral possibilities that may create, but the validity of his ideas is by now quite well-established. We think of Theory Y as providing a framework for what we call ‘enlightened leadership’.

Theory Y, on the other hand, acknowledges the possibility–indeed the likelihood–that employees may be ambitious, self-motivated and anxious to accept greater responsibility for the content, method and outcome of their work. It assumes that, given the chance, employees may well desire to be creative and forward-thinking in the workplace, thus obviating the need for excessive work rules, giving workers freedom to perform at their best, increasing productivity and generally making life wonderful for one and all—OK, that may be a bit of an overstatement. McGregor urged only that leaders and managers be open to a more optimistic perception of workers and the behavioral possibilities that may create, but the validity of his ideas is by now quite well-established. We think of Theory Y as providing a framework for what we call ‘enlightened leadership’.

The late Edgar Schein, MIT Professor Emeritus and preeminent organizational culture guru of the last half-century, pointed out that a given manager’s embrace of either the X or Y theory determines the managerial strategy that particular manager will employ in interacting with those under his or her supervision. Thus, the Theory X manager inherently distrusts workers and is likely to employ control mechanisms such as time clocks, frequent monitoring, strict limits of authority, excessive policies and procedures, etc and generally communicate a lack of confidence and trust in the workforce. Micro-management is an apt descriptor. Over time, Schein observed, workers will react by becoming more passive, thus confirming in the manager’s mind the accuracy of those initial assumptions.

Theory Y managers, conversely, are most likely to promote the alignment of individual and organizational goals, delegate more responsibility, and generally function more as collaborators and coaches than hall monitors. This approach has been observed by McGregor, and legions of others since, to elicit greater creativity, motivation and higher performance levels—the sort of positive productive behaviors we should be striving for.

Thus, we can reasonably conclude that attitudes and assumptions about workers can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Management practices designed around expectations of employee behavior tend eventually to produce the expected behavior. Thus, we should consider the obvious logic of organizing managerial strategy around the behavior we most prefer rather than that we might be inclined to predict. The attitudes, beliefs and behavior of the leader are, of course, critical factors here. More on that a bit later.

By embedding these practices—indeed this mentality—in the organizational culture, we reify the positive behaviors that have been shown conclusively to increase engagement and improve performance at all levels of an enterprise.

Alternatively, we could—as many apparently have—retreat to the definition of leadership attributed to ancient Chinese Philosopher Lao Tzu. To wit:

“Leadership is the ability to hide your panic from others.”

Nah—there’s gotta be more to it than that–you can’t fake it.

Leadership, as we define it, is the art of influencing others to adopt attitudes, beliefs and behaviors that enable perpetual improvement and the achievement of mutual goals. To improve the performance of any enterprise, its leaders must positively influence the day-to-day performance—or behavior—of its individual constituents. That’s it. McGregor shows us the way, but prior even to McGregor’s publication of The Human Side of Enterprise (1960), Albert Einstein famously articulated what should still be considered the essence of effective leadership:

“Setting an example is not the main means of influencing others,

it is the only means”.

- So we know all this—and we’ve known it for literally decades. Why then, it’s reasonable to ask, do we continue to see such genuinely pitiful results year after year in the proliferation of surveys, studies, reports, etc published by the likes of The Gallup Organization, Harris Interactive, Stephen Covey, Development Dimensions International, The Corporate Executive Board, Towers Perrin, LRN, Deloitte, Booz-Allen, Quantum Workplace, all manner of researchers and academics, and on-and-on ad nauseam—all of which produce remarkably similar outcomes revealing a stunningly low engagement level of the workforce and little in the way of encouragement about the current or future state of the business art?

Here’s a sampler:

- Just a tad over a third of the workforce knows what their organization is trying to achieve and why, and four out of five don’t fully trust the organization they work for (Harris/Covey);

- less than half know what is expected of them at work, and fewer than three in ten think their opinions count at work (Gallup);

- only about three in ten are engaged at work, leaving the other six or seven not engaged, and two of those are ‘actively disengaged’ (Gallup);

- fewer than 10% say they work in a company with a strong set of values (LRN); and

- a staggering 96% say some form of culture change is needed within their organization (Booz-Allen).

Not a pretty picture—and it’s not getting much better. The most recent edition of the massive Employee Engagement Trends Report published by Quantum Workplace determined that the two most frequently cited areas of concern among the study’s more than 600,000 participants were “lack of recognition of their contributions to the success of their organizations”, and the “absence of professional growth and career development opportunities”. And yet Quantum identifies these two attributes as among the “top drivers of engagement”. Further, Gallup’s landmark report State of the American Manager highlights the strong connection between engagement and “business outcomes that are essential to an organization’s financial success”, but also points out that over the past 12 years, the low rate of employee engagement has “barely budged”, and that only 35% of managers are themselves engaged at work.

Want more? A study of 1200 employees, managers and executives released a few years ago by VitalSmarts® co-founders Joseph Grenny and David Maxfield reveals the persistent breadth of the disconnect between workers and leaders. Though leaders say they want “innovation, candor and teamwork”, workers report what is actually valued is “obedience, predictability, deference to authority and competition with peers”.

The gap revealed in the study between workers’ view of their corporate culture and that of their leaders exposes a stark disconnect between leaders and workers. Unsurprisingly, the higher one’s perch in the organizational hierarchy, the rosier one’s view of life within the enterprise.

Of near equal concern is the study’s finding that only 9% of employees have a favorable opinion of their culture, and even among the leadership group just 15% viewed their culture favorably. Yikes.

Let’s be clear: subpar performance is most always associated with low workforce engagement. Low workforce engagement is a function of poor culture. Poor culture is the product of lousy leadership.

It’s that simple.

Could the desperate need for a new leadership paradigm be more obvious?

A wealth of other studies document the positive effects of increasing engagement levels—from reduced turnover and absenteeism, to improved safety records, increased revenue, higher levels of profitability and greater stock prices.

And the numbers are impressive. A study by the UK-based Barrett Values Centre of the share price performance of the top twenty public companies in the annual Best Companies to Work for in the USA survey over a ten-year period revealed an average annualized return of nearly 17% versus less than 3% for the S&P 500 as a whole. And a Gallup Q12 Meta-Analysis revealed an engaged workforce yielded 21% and 22% annual increases in productivity and profitability respectively and that companies with an engaged workforce outperform their less engaged competitors by as much as 220%.

Gallup also tells us that companies with highly-engaged workforces surpass their less-engaged peers by nearly 150% in earnings-per-share, and enjoy an EPS growth rate more than quadruple that of the peer group at large.

We could go on, citing numerous other studies documenting even more dramatic results, but there’s simply no longer any doubt that increased levels of workforce engagement are directly linked to enhanced financial performance. In fact, we are firmly convinced by the sheer weight and volume of the evidence that positive culture change is at once the greatest opportunity and most direct path to improved organizational performance for the vast majority of enterprises.

It’s the Ultimate Strategic Plan—full stop.

But still, engagement rates remain mired the bottom half of the 30s% range year-after-year, and unfortunately, organizational culture is still hands-down the least understood and most under-managed attribute of virtually all organizations. And, of course, the pandemic added yet another set of complicating variables to the mix.

Clearly, organizations and their leaders are broadly failing to effectively communicate their purpose, values and goals to those through whom they expect to fulfill them, much less enlist them in the effort. The alarming workforce engagement deficit evidenced in the studies above has become a hot-button issue in frantic search of a solution. Don’t take our word for it—in a Deloitte survey of 3,300 business leaders, 87% cited “engagement” as their top issue, and in a recent report released by The Conference Board, “human capital” was cited as the number one challenge for CEO’s around the world, with “employee engagement” further identified as a key priority and strategy to address that challenge. And finally, in Deloitte’s 2019 Global Human Capital Trends survey, 84% of the over 9,000 executives participating say they need to “rethink their workforce experience to improve productivity”, and 80% believe the “need to develop leaders differently”. In other words, they’re contemplating the major overhaul of their own organizations and their approach to leadership.

Obviously, there’s no lack of awareness of the problem. Leaders know all too well they have a massive problem. Yet engagement numbers remain stubbornly static at unacceptably low levels.

But why?

To understand why, we should perhaps revisit Confucius’ Essence of Knowledge. We may know very well the X and Y of leadership and fully understand the sagacity of Einstein’s ‘influence-by-example’ admonition—let’s face it, it ain’t exactly Relativity. But can we say that most leaders act in sync with that knowledge?

If the answer is ‘no’—and it is—we’re back to ‘why?’

Professor Schein observed that though organizations may overtly espouse the virtues of teamwork, empowerment, communication, consensus, flat structures, etc, the harsh reality is that, beyond the lip service, these practices don’t truly exist in most corporate cultures because such cultures are built upon solidly embedded assumptions of hierarchy, control, privilege and prerogative, limited communication and the presumption that ‘management’ and ‘employees’ exist in a perpetual state of tension and conflict. Schein goes on to point out that in most cases these values are so deeply entrenched that they can only be changed through “…major organizational transformation…”.

So that’s why.

Leadership is at once the problem and the solution.

Maybe that’s the reason US businesses spend tens of billions of dollars annually on leadership-based curricula according to the American Society of Training and Development. And a Google search for ‘leadership books’ yields more than 2.5 million hits–a lot more. But still workforce engagement languishes at the low end of the continuum. Turns out that ‘walking the talk’ is far more difficult than we might have imagined.

Richard Barrett, founder of the Barrett Values Centre, puts it this way

“Simply put, the culture of an organization is a reflection of the values and beliefs of the leaders. Who you are as a leader determines the corporate culture. Therefore, if you want to change the culture, either you must change, or you must change the leader. Cultural transformation begins with the personal transformation of the leaders; organizations do not transform [unless] people do.”

Or, as comic-strip philosopher, Pogo, famously sounded the alert:

sacredTo paraphrase Peter Drucker, ‘rank confers neither power nor privilege—it imposes responsibility’. But we cannot suffer the delusion that those perched atop the hierarchal heap will enthusiastically cede the power and perks to which they have become accustomed. Those possessed of power like it—a lot. There are still those among us to whom the corner office and the reserved parking slot are sacred symbols of their status and authority. Since, as Dr Barrett highlights above, organizational culture reflects the values of an organization’s leadership, this is where we must concentrate our attention if we are to have any reasonable expectation of meaningful change.

Humans are hard-wired to resist change (Google amygdala for details), but this indeed is where ‘the rubber meets the road’. The reality is that extant in every system is a palpable organizational inertia militating against fundamental change—the status quo is the default option absent the implementation of conscious and consistent change initiatives affecting every constituent of the organization—in a word, transformation.

A bit more blunt than either Barrett or Drucker is the late Herb Kelleher, co-founder and long-time CEO of Southwest Airlines:

“I forgive all personal weaknesses except egomania and pretension…power should be reserved for weightlifting and [speed] boats; leadership is about responsibility…the only thing your competitors can’t eventually duplicate is your culture”

The tipping point must be a genuine embrace of the reality that all stakeholders are the beneficiaries of an organizational culture that recognizes and rewards leadership and initiative at all levels. Ralph Nader provides a relevant insight:

“…the function of leadership is to produce more leaders,

not more followers”

As mentioned above, we must acknowledge the implicit difficulty of effecting behavioral change at the highest levels of any enterprise, but also simultaneously recognize that doing so is the essential prerequisite to positively impacting behavior throughout the organization. Make no mistake—successful workforce engagement and the alignment of individual and organizational goals requires strong and adaptive leadership skills and unwavering commitment. The faint-of-heart need not apply.

So how do we go about a ‘hearts-and-minds’ makeover of senior leaders? The short—if circular—answer is ‘by transforming the culture’, which, of course, is largely accomplished by enlightening the leadership. Once awakened on a conscious level to the realization that positive culture transformation and leadership enlightenment are inextricably connected, we begin to see the way forward. This should be patently obvious given that we are, after all, embracing descriptions of leadership and culture as essentially mirror images—two sides of the same coin, if you like. So it becomes crystal clear that the process of transforming organizational culture necessarily involves the simultaneous development of enlightened leadership. You simply cannot achieve one without the other—at least not in any truly effective or sustainable way. In fact, it has become increasingly apparent that the processes of enlightening leadership and transforming culture are implicitly one and the same, and that what we call the Core Dynamics of our organizational culture model are entirely about leadership.

This is not to say that every leader will be open or able to adjust to or ultimately adopt an enlightened approach which recognizes leadership as a role, not a rank. But we may as well find that out sooner than later. As Dr Barrett pointedly suggests, leaders must either change or be changed if the culture is to advance. Tough decisions may well prove unavoidable.

If this all sounds like an indictment of organizational leadership broadly, it probably is—at least as to the leadership of about two-thirds of American organizations. Believe it or not, engagement levels in the rest of the world are even worse, and not by a little. But we can take no solace in those statistics, or being the ‘best of the worst’, if we’re to focus on what can only be characterized as a crucial issue facing a substantial majority of US companies and institutions. In this, we are competing only with ourselves–but in the process, improving our ability to compete with others.

Fortunately, this is a problem that can be seized as an opportunity to effect permanent solutions that are at once comprehensive and self-perpetuating. Most leaders will embrace such an approach once they realize it needn’t be threatening to anything but intransigence and sub-optimum performance. We know this to be doable, but no one is promising easy. In the end, Enlightened Leadership cannot be taught or trained—it must be instilled.

And we should dispel any mistaken notion that what’s advocated here is defined by altruism, or some sort of ‘touchy-feely’, ‘feel-good’ approach, or an exercise in ‘Kumbayah’. There will be neither group-hugs nor trust-falls, and we regard ‘team-building’ as implicit to our daily activities—not just a one-off trip to the local pub, escape room or climbing wall. Results in the form of improved performance up and down the organization are the purpose of our every act. An enlightened approach is by far the best–perhaps the only–path to that end.

What we propose is not a one-size-fits-all template, but rather a practical, comprehensive, tailored program to evaluate, elevate and perpetuate—ie, continuously improve—the embedded culture and leadership capacity of any committed organization, in sync with its own unique character and strategic requirements so as to optimize performance whatever its charter. That’s a mouthful, but these attributes are far too mission-critical to be left to chance. Citing Dr Schein one last time:

“The only thing of real importance that leaders do is to create

and manage culture”

Transformation must of necessity be undertaken one step at a time—in building-block fashion, if you like. Starting with the senior leadership group and working our way through the entire organization, evaluating natural workgroup dynamics, defining both the currently prevailing culture and the culture most desired by stakeholders at all levels while gradually engendering an understanding of organizational culture and its dynamic elements throughout the enterprise. In larger, diversified or geographically dispersed entities, it is inevitable that some number of ‘subcultures’ will exist. These may well be important to preserve—if not necessarily in their current iteration—but we should ensure that they exist under the aegis of a common organizational vision and values set that applies universally throughout the organization.

Next, the introduction of targeted programs and processes to begin morphing the culture in the desired direction, again employing a systematic approach organized into digestible chunks. And finally, institutionalizing the perpetuation of the culture we have created to assure permanence. Consistent reinforcement is the indispensable mandate. If we’ve completed the forgoing steps effectively, this critical process will be our least challenging task.

Obviously, it’s not possible to adequately describe what is by its very nature an arduous, often discomforting, and always time-consuming process in a few paragraphs—particularly a process that is customized to the unique needs of each particular organization, and often discrete units within as well.

This is an incremental process, but there can be no ‘half-way’, or ‘toe in the water’ commitment here. If an organization is not ready to make an ‘all-in’ leap in its quest for ever better performance, it may be well advised to take a step back from the precipice rather than risk likely—perhaps certain—failure that may prove more damaging than doing nothing at all.

Otherwise put, it ain’t easy, but it’s worth it. Think of it as the ultimate expression of the enlightened self-interest of the organization, its leadership, and all of its stakeholders.

In Greek mythology, Prometheus was the creator of mankind who risked the ire—and incurred the wrath—of Zeus to give humans the gift of fire that they might advance. Like Prometheus, we seek to provide a spark that lights the way to advancement. And we recognize and accept that an occasional Zeus may take umbrage. But we are ever informed by the words of hockey great Wayne Gretsky:

“You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.”

#Think About It.