McGregor's Theories X&Y

Douglas McGregor’s Theories X and Y of workforce behavior, developed in the 1950s and ‘60s at MIT, are implicit in much of what has since been written about leadership, management and organization development.

Theory X embodies the assumption that workers are inherently lazy and will avoid work if and where they can. Thus, the theory goes, employees need to be closely supervised and comprehensive systems of controls developed. A rigidly hierarchical structure is required with a narrow span of control at each level. According to Theory X, employees will show little ambition without an enticing incentive program or fear of punishment, and will avoid responsibility whenever they can. Employees—perhaps people in general—are not to be trusted, and the allocation of blame is a major supervisory function. You may hear this referred to as accountability, but as Harvard’s Pasi Sahlberg puts it,

“Accountability is what’s left when responsibility is subtracted”

Of course, the notion that others are motivated only by coercion or monetary reward leads inevitably to an authoritarian culture and leadership style, the oppressive pessimism of which subverts morale, engagement and productivity. This seemingly anachronistic mindset—and its tacit assumption that ‘leadership’ and ‘management’ are somehow genetically immune to these behavioral influences—has been with us since well before Adam Smith, but is even today not as uncommon as we might like to think. The ‘we/they’ paradigm is alive and unwell here in the third millennium.

Theory Y, on the other hand, acknowledges the possibility that employees may be ambitious, self-motivated and anxious to accept greater responsibility for the content, method and outcome of their work. It assumes that, given the chance, employees may very well desire to be creative and forward-thinking in the workplace, thus obviating the need for excessive work rules, giving workers freedom to perform at their best, increasing productivity and generally making life wonderful for one and all—OK, that may be a bit of an overstatement. McGregor urged only that leaders and managers be open to a more optimistic perception of workers and the behavioral possibilities that may create, but the validity of his ideas is by now quite well-established.

Theory Y, on the other hand, acknowledges the possibility that employees may be ambitious, self-motivated and anxious to accept greater responsibility for the content, method and outcome of their work. It assumes that, given the chance, employees may very well desire to be creative and forward-thinking in the workplace, thus obviating the need for excessive work rules, giving workers freedom to perform at their best, increasing productivity and generally making life wonderful for one and all—OK, that may be a bit of an overstatement. McGregor urged only that leaders and managers be open to a more optimistic perception of workers and the behavioral possibilities that may create, but the validity of his ideas is by now quite well-established.

We think of theory Y as providing a framework for what we call Enlightened Leadership, a key component of our approach to building an engaged culture.

The late Edgar Schein, MIT Professor Emeritus and perhaps the preeminent organizational culture guru of the last half-century, pointed out that a given manager’s embrace of either the X or Y theory determines the managerial strategy that particular manager will employ in interacting with those under his or her supervision. Thus, the Theory X manager inherently distrusts workers and is likely to employ control mechanisms such as time clocks, frequent monitoring, strict limits of authority, excessive policies and procedures, etc and generally communicate a lack of confidence and trust in the workforce. Micro-management is an apt descriptor. Over time, Schein observes, workers will react by becoming more passive, thus confirming in the manager’s mind the accuracy of those initial assumptions.

Theory Y managers, conversely, are most likely to promote the alignment of individual and organizational goals, delegate more responsibility, and generally function more as collaborators and coaches than hall monitors. This approach has been observed by McGregor, and legions of others since, to elicit greater creativity, motivation and higher performance levels—the sort of positive productive behaviors we should be striving for, ie, Enlightened Leadership.

Thus, we can reasonably conclude that attitudes and assumptions about workers can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Management practices designed around expectations of employee behavior tend eventually to produce the expected behavior. Thus, we should consider the obvious logic of organizing managerial strategy around the behavior we most prefer rather than that we might be inclined to predict. The attitudes, beliefs and behavior of the leader are, of course, critical factors here.

By embedding these practices—indeed this mentality—in the organizational culture, we reify the positive behaviors that have been shown conclusively to increase engagement and improve performance at all levels and aspects of an enterprise.

–KWM 2019

Gallup Announces 'Record-High Employee Engagement' in US...Great News, Right?

Kenneth Miller | February 2020

Earlier this month, Gallup announced the results of it’s latest annual employee engagement survey. This year it was able to report the highest level of US workforce engagement it has recorded since the survey was launched some two decades ago. This is important because Gallup’s latest meta-analysis of studies covering nearly 2 million employees reveals conclusively that organizations with high engagement outperform those without —by a ton.

Some of the engaged vs disengaged results:

- 41% lower absenteeism

- 70% fewer safety incidents

- 40% fewer defects (quality)

- 17% higher productivity

- 20% higher sales

- 21% higher profitability

Clearly, engagement matters—a lot. So record-high workforce engagement is a good thing.

But the not-so-good thing is that this ‘record-high’ engagement level is only 35%—up from 34% in 2018. In other words, 65%—nearly two-thirds—of the US workforce is not engaged at work. Does anyone find this remotely acceptable?

Let’s face a couple of salient realities :

- Low workforce engagement is the result of poor organizational culture.

- Poor culture is the result of lousy leadership.

Yes, the workforce is undergoing generational change—but that tired complaint dates back at least to Socrates—and yes, we’re in the midst of a technological renaissance and work in the future may not at all resemble that of the past or even the present. But so what? It’s no secret that change is the universal constant. It’s the job of leadership to see these trends, adapt, and take advantage of them to the benefit of the organizations they lead—full stop.

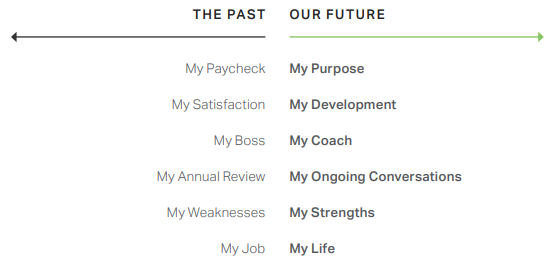

Gallup characterizes the transitioning priorities of today’s workforce this way:

This provides a virtual template for adaptive organizations and effective leadership:

- purpose-driven, values-governed organizations in which the alignment of individual and organizational goals are a top priority

- leadership that understands that ‘leader’ is a role, not a rank, and that the relative success of the group is dependent upon the individual success and advancement of its members

- the realization that performance improvement is a subject of the daily dialogue, and that the workforce is most effective when encouraged to function more as empowered chessmen than checkers—capitalizing on their individual strengths and unique abilities

So, yes, any improvement in engagement is a positive—’Better’ is always the objective—but, as Gallup points out:

“The percentage of engaged employees in the US is still far too low.

There is plenty of room for improvement.”

Uh…yeah.