Simple? Maybe...Easy? Nope.

Kenneth Miller | February 2018 | last updated October 2023

Culture is hands-down the least understood and most chronically under-managed attribute of the vast majority of organizations.

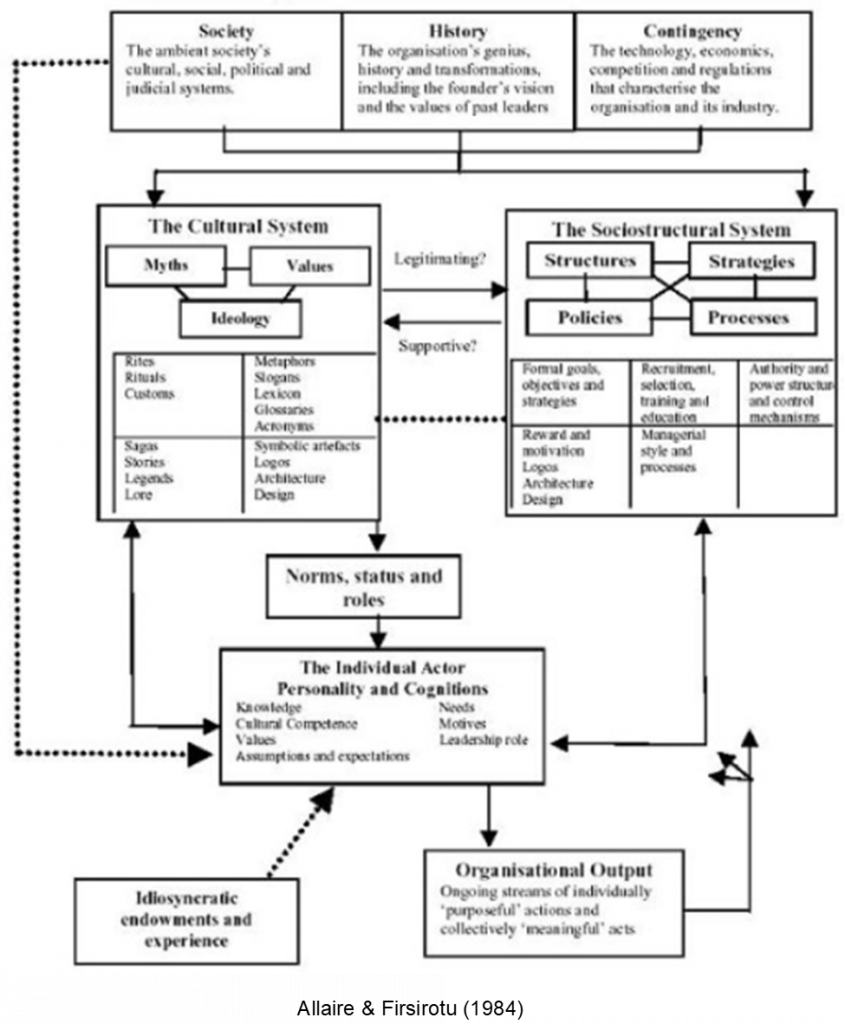

If we accept the accuracy of the above statement—and we do—we must ask ourselves, why? Legions of academics, researchers, and others have studied the matter in great depth over many decades, and have promulgated a massive body of research papers, statistics, and models to describe organizational culture, presumably to help the rest of us understand. Here’s an example:

If a bit ‘fuzzy’, this is no doubt a very good depiction of how various cultural influences interact to affect organizational performance, and the direct proximity of the ‘Individual Actor’ to ‘Organizational Output’ should inform our thinking. But—with apologies to Allaire & Firsirotu—let’s just admit that visually it sort of resembles a kids’ placemat at, say, Applebee’s.

Yes, this is arcane stuff, but we must find a way to make it comprehensible and user-friendly or it won’t be of practical utility in the real world. Many companies and other organizations ambitiously set off on cultural transformation initiatives, only to see the majority fizzle-out after some period of occasionally heroic effort.

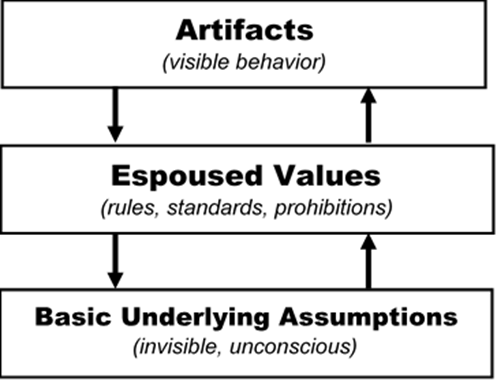

The late MIT Professor Emeritus Edgar Schein, arguably the most widely recognized and respected contemporary organizational culture guru, modeled it thusly:

By organizing cultural elements into three categories, Schein has established a framework within which the nature of culture and its components can be more readily discussed and understood. It is interesting to note his differentiation between ‘espoused values’—what we say—and the visible behavior he labels ‘artifacts’, ie, what we do. We may discern a tinge of perhaps unintended cynicism, but the point is an important one. Organizations do indeed tend to pay lip service to what they perceive to be all the ‘right’ values, but when the behavioral rubber meets the cultural road—well, the traction often tends to disappoint. Or as Schein put it in The Corporate Culture Survival Guide:

“We can espouse teamwork, openness of communication, empowered employees who make responsible decisions, high levels of trust, and consensus-based decision making in flat lean organizations until we are blue in the face. But the harsh reality is that, in most corporate cultures, these practices don’t exist because the cultures were built on deep assumptions of hierarchy, tight controls, managerial prerogatives, limited communication to employees and the assumption that management and employees are basically in conflict anyway…These assumptions are likely to be deeply imbedded and do not change just because a new management group announces a ‘new culture’…if such assumptions really are to change, we need a major organizational transformation effort.”

Amen, Professor.

But how can we ensure that such an effort can sustainably ‘stick’?

We believe that the CultureDYNAMICS model provides a practical, user-friendly approach to understanding and improving organizational culture. Based in part on the work of Professor Schein, but also Gerry Johnson and Kevan Scholes, among others, the elements of culture—which we call ‘Dynamics’—are, like Schein’s model, grouped into three interactive categories:

Core Dynamics

Vision and Values–the non-negotiable cultural prerequisites that define the organization–its purpose and ethos

Organizing Dynamics

Organization Structure, Mission, Strategy, and Methods–the Cultural elements designed to establish the managing mechanisms considered necessary to the realization of the organizational Vision/Purpose

Organic Dynamics

Informal Power Structures, Narrative & History, Symbols, and Habits–the generally informal underlying cultural attributes that develop and evolve over time–most often not by conscious design–and flesh out the character of the organization in perhaps subtle but critical ways

We can think of the Core Dynamics as akin to Professor Schein’s Espoused Values; the Organizing Dynamics somewhat like his Artifacts, and the Organic Dynamics as similar to the Basic Underlying Assumptions in the Schein model. In each case, however, we go on to identify the specific component cultural elements compromising the various categories, making the entire construct more comprehensible, practical, and generally user-friendly. The real difference lies in the extent to which this all becomes part of the lexicon of the daily dialogue.

The CultureDYNAMICS organizational culture model can be a powerful tool, facilitating an understanding of culture generally, and providing a framework to evaluate the cultural status quo and plan improvements in existing cultures. Fully implemented, the CultureDYNAMICS program lays out a step-by-step methodical system for transforming any culture and perpetuating a sustainable positive organizational culture.

So, hopefully we have succeeded in making culture a bit simpler to understand.

But does that mean that positive culture transformation will thenceforth be easy?

Sorry, the answer is still “nope”.

As we highlighted at the top,

Culture is hands-down the least understood and most chronically under-managed attribute of a vast majority of organizations

but it is also true—and the evidence is compelling—that,

Positive culture change is at once the greatest opportunity and most direct path to improved performance for virtually any organization.

So how, one must wonder, can these phenomena be permitted to co-exist? We needn’t ponder this question at any length. In our continuing quest for simplicity, the answer is—simply—Human Nature.

Improving an organization’s culture requires change—perhaps upheaval. But humans are hard-wired to resist change (Google amygdala for details). And the reality is that extant in every system is a palpable organizational inertia militating against fundamental change—the status quo is the default option absent the implementation of conscious and consistent change initiatives affecting every constituent of an organization—in a word, transformation.

Further, we cannot suffer the delusion that those perched atop the hierarchal heap will enthusiastically cede the power and perks to which they have become accustomed and consider themselves entitled. Those possessed of power like it—a lot. There are still those among us to whom the corner office and the reserved parking slot are important symbols of status and authority.

So, comic-strip philosopher Pogo had it right in sounding his famous alert:

“We have met the enemy, and he is us!”

Richard Barrett, founder of the Barrett Values Centre, puts it this way:

“Simply put, the culture of an organization is a reflection of the values and beliefs of the leaders. Who you are as a leader determines the corporate culture. Therefore, if you want to change the culture, either you must change, or you must change the leader. Cultural transformation begins with the personal transformation of the leaders; organizations do not transform [unless] people do.”

To paraphrase Peter Drucker, ‘rank confers neither power nor privilege—it imposes responsibility’.

But Herb Kelleher, co-founder and long-time CEO of Southwest Airlines, is a bit more blunt than either Barrett or Drucker, to wit:

“I forgive all personal weaknesses except egomania and pretension…power should be reserved for weightlifting and [speed] boats; leadership is about responsibility…the only thing your competitors can’t eventually duplicate is your culture.”

There’s that word again—responsibility. Indeed, we believe it is a fundamental responsibility of leadership to put aside the petty parochialism of personal privilege and act in the interests of the greater organization. The tipping point must be a genuine embrace of the reality that all stakeholders are the beneficiaries of an organizational culture that recognizes and rewards leadership and initiative at all levels.

Yes, leadership is the problem.

It’s also the solution.